|

“I don’t know why my Hydrangeas don’t flower” is one of the great conundrums that are handed to me by clients. As with all things, I never know exactly, nor do I have an clear answer, I can only offer that coming to understand these things takes place in the process of experiencing and working with the garden. This question almost always comes while looking upon a Bigleaf Hydrangea (Hydrangea macrophylla). Immediately one asks how it may have been pruned, the gardens history and care, considers the soil, and how cold it was the past winter knowing that Hydrangea macrophylla often experiences tip dieback where you loose the flower buds to the winter’s cold.

A week or two ago I ordered Michael Dirr’s latest edition of “Hydrangeas for American Gardens” (2020) to begin a little study on Hydrangea. I am finding them becoming so popular, even in my own preferences, that some study is a worthwhile investment. At least at the start of this, it was Hydrangea paniculata and its cultivars that I am most interested in. However, a little tidbit caught me while reviewing Dirr's work on Hydrangea: Bailey (1989a) provides climatic data for the native habitats that explain Hydrangea macrophylla sensitivity to certain extremes. Honshu enjoys more than 5 months of frost free temperatures. The mean low and high temperatures are 31 and 47 degrees F in January and 72 and 85 F in August, respectively…The conclusions are obvious: H. Macrophylla prefers moderate temperatures…(73). Most of Dirr's writing on macrophylla is based on studies done at his University in Athens, Georgia and from research done in North Carolina. Even at those southern locations, some of the named cultivars he writes of as not surviving the cold are names I recognize as macrophylla cultivars in WNY nurseries. From this I leapt to: “All these Hydrangea I see that don’t flower - they probably just aren’t hardy enough to begin with.” So. I thought I would do a little research on the cultivars most readily available to me right now and find what research I could on hardiness data. One key is understanding the “remontants” or re-bloomers. These bloom multiple times because they will bloom on this seasons new wood as well as older wood. A hydrangea that doesn’t bloom on new wood is dependent on old wood to over winter for its flower buds. When they are killed off by frost, no flowers. But with re-bloomers, the old wood can die back to the ground but still produce flowers that season on its new wood. I believe most traditionally we think of Hydrangea macrophylla as a plant that "blooms on old wood." The Study: Generally, and this is new to me, it seems that plant breeders characterize Hydrangea macrophylla as “undependable.” Thus my curiosity of "why is this such a commonly used plant in WNY?" To disclose, this isn't the deepest research. A few hours. I made the best sense of things reading a couple blogs, Dirr's latest edition of "Manual of Woody Plants," Dirr's latest on Hydrangea's, and a few wholesale catalogs and nurseries I have here in the office. Here is what I have found on the cultivars:

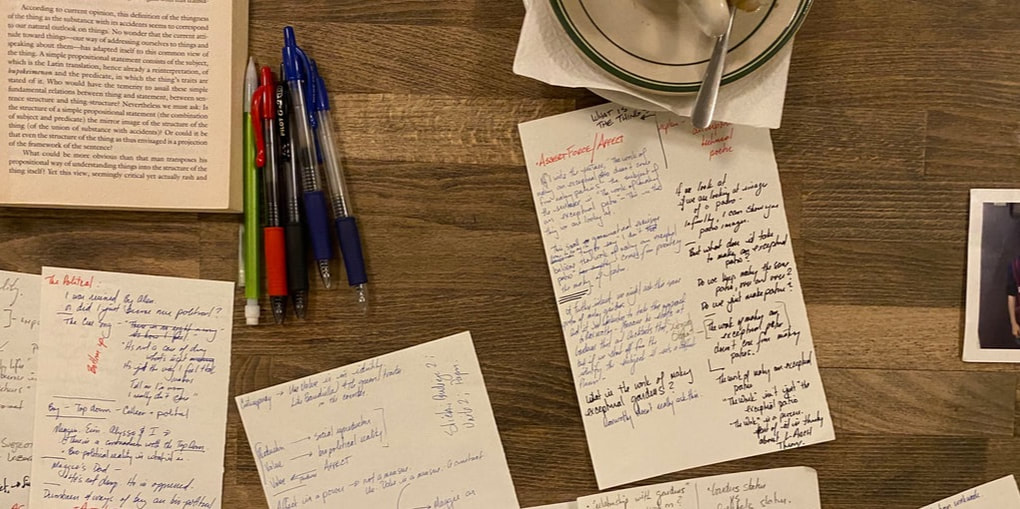

What I generally find in the literature combined with my experience is that Hydrangea macrophylla's flower buds, those on old wood, are most often probably killed off. A Hydrangea can be listed as cold hardy zone 4 (for example) but this just means the plant survives, it doesn't mean the flower buds survive. It seems that even all the new rebloomers and remontants, while exciting in concept, they generally seem to be written of as disappointing - however the most recent 'Bloomstruck' series appears to be the best yet and worth my experimentation. The thing with a rebloomer is, it becomes a plant that blooms on this season's wood, and thus later in the season, which means a shorter flowering season. It seems the recent improvements in Hydrangea arborescens are perhaps more worth exploring. Just some notes. Post Script. April 6th, 2021. I have been watching the Hydrangea this spring. I can see that possibly the buds on the tips get through the winter as they have the opportunity to acclimate to the deep cold of winter. But now, the beds are starting to swell at the end of March, beginning of April. The inevitability of a hard frost here in early April - well - these swelling buds are probably most susceptible to frost/cold damage now. More so now than the first week of February. 3/4/2021 Morning's Notebook.Some notes and bullets.

3/1/2021 Lesser Celandine1. Lesser Celandine (Also called "Fig Buttercup") |

AuthorFrom Matthew Dore, the "I" voice of Buffalo Horticulture and "The Buff Hort Project." Archives

April 2022

Categories |

Telephone(716)628.3555

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed