|

2/27/2021 In Defense of The Lawn - Episode 51. The lawn hasn't grown up as a raw obsession America has with its lawns as the story may often be told. The desire for the lawn doesn’t come first. The lawn starts in a development practice where we clear the land, level it, grade it, drain it, build roads and urban infrastructure, build homes, and then put the soil back in place. That soil can’t be left bare. All soil, as part of the finishing of development, must be covered in turfgrass, both for cleanliness and to prevent the erosion of soil. If the soil was allowed to erode away, it would quickly clog up all the constructed storm water infrastructure and alter the local waterways with sedimentation. Point being, the monsters of American culture aren’t out there fetishizing lawns so much that paradise is being paved over for it alone. Lawns, in their original production and construction, are about inexpensive and effective land development.

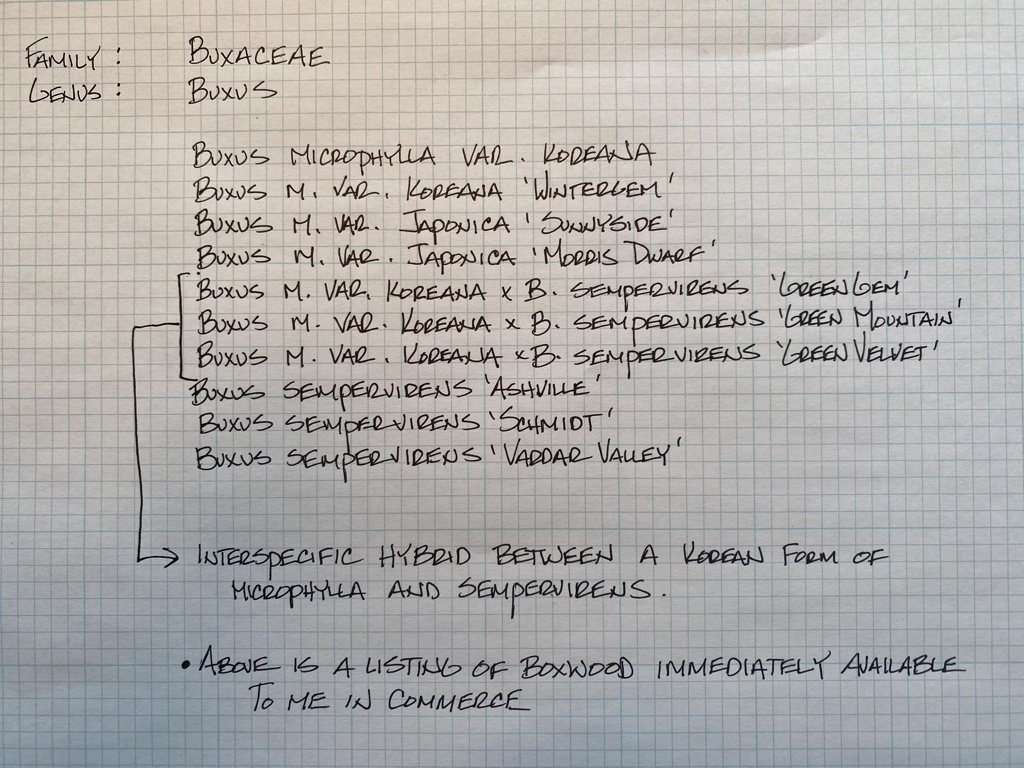

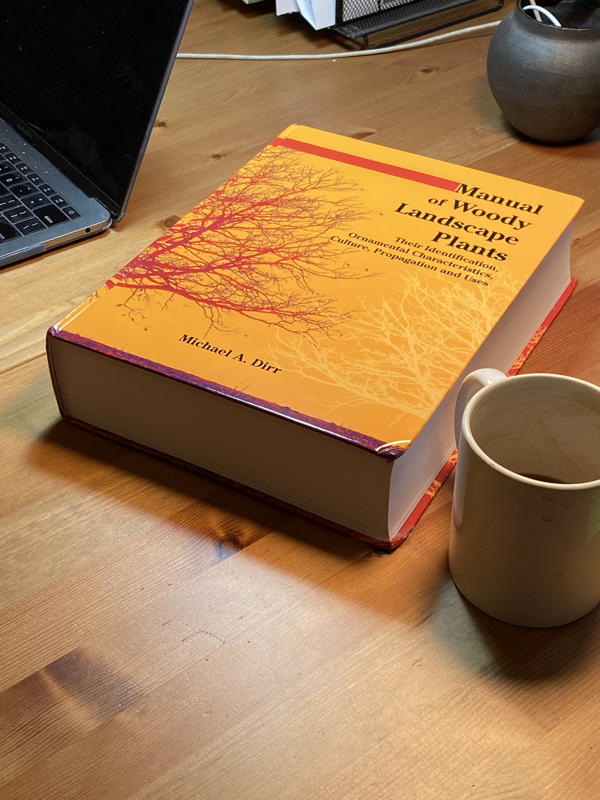

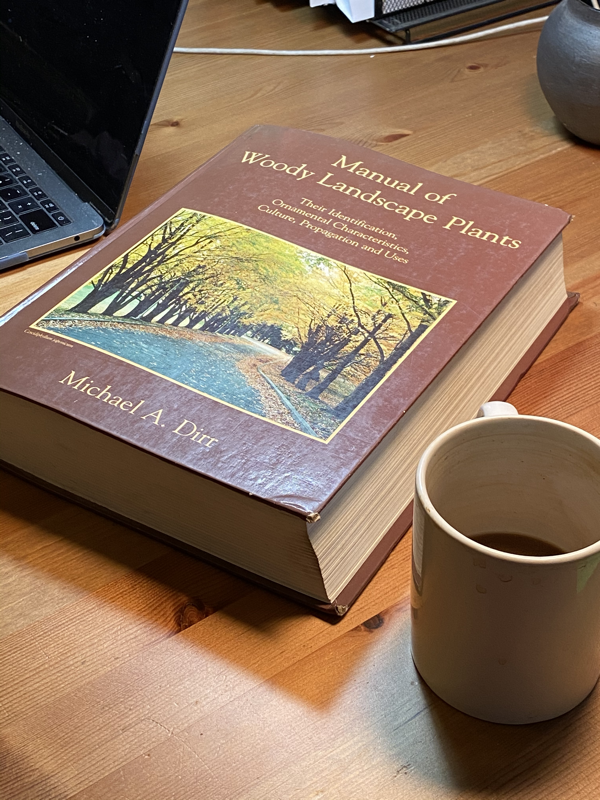

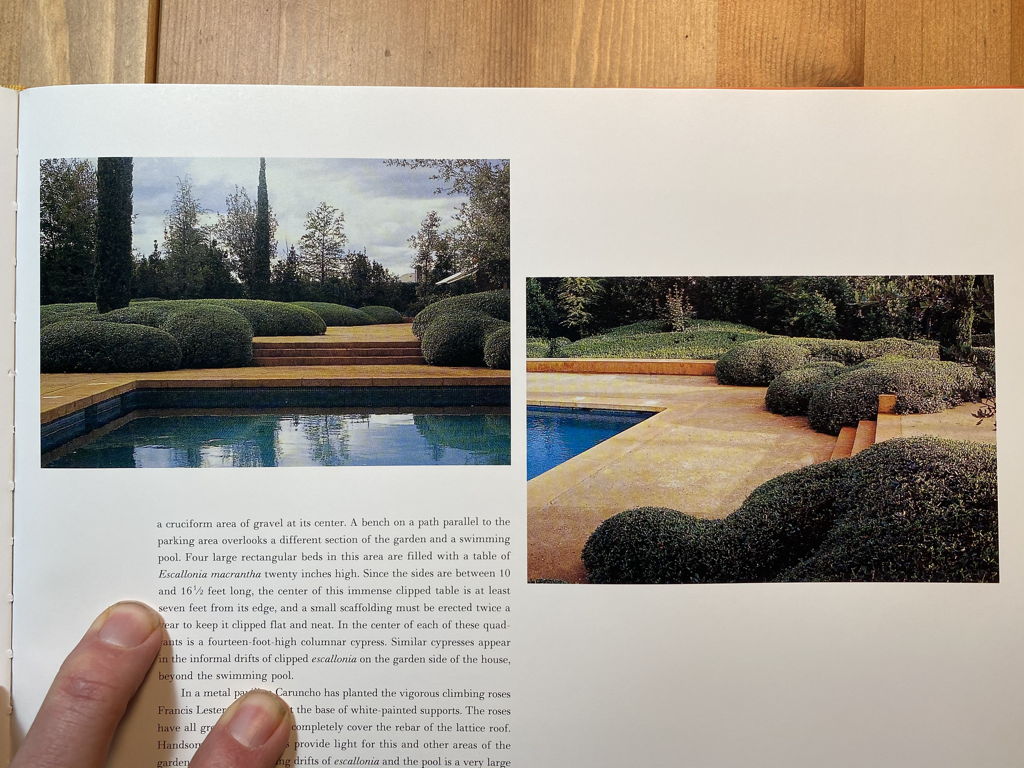

2. Andrew Jackson Downing followed by Olmstead in the mid to late 1800s advocated for open spaces, as if each suburban home was set in a communally maintained park of which individual homeowners tended their own piece. But by the time Levittown (recognized as the first mass-produced suburb, a planned community for veterans returning home from WWII) was conceptualized and developed in the late-1940s, the imagination of the lawn was no longer a socialist dream of the romantic American landscape. By this time the lawn’s utopianisms we reduced to the dreams of developers putting out inexpensive housing and developments suited for the automobile. 3. The development history today's homeowners are a part of is outside their agency. There are people who aren't obsessed with their lawns, they just want to give care to their spaces. I want people to feel good about giving care to their landscape and grounds and not have to face the shaming, labeling, and reduction that some like to place on them as if they are just mindless conformists to The American Lawn Aesthetic. A healthy lawn may surround someone's home because they care for it. Giving care to their space might be what feels good for them. While Boxwood, in a certain audiance, are certainly seen as worn out and overused because of how they fill the suburban niche of "evergreen plant that is deer browse resistant," I have been exploring and finding, for the first time in my career, ways I like to use them. This comes from recognizing them as a plant that tolerates the difficult dry shade gardens we are working with all the time in The City and also seeing them as a plant with an extensive tradition and history in the garden.. For the first time in several years I pulled out my "Dirr," as we call it generally; Michael Dirr's "Manual of Woody Landscape Plants," the original edition put out in 1972 I believe, which has been the standard reference on woody ornamentals ever since. I work with the 5th edition from 1998, however, because of the excitements I experienced in there today, I just ordered the latest edition, the 6th, from 2009. Dirr - I think it somewhat funny - because of my simultaneous readings of the NYT literature lists - has a way of compiling a really interesting texts. Its a typical reference book, there are chunked together points on "culture," "hardiness," "diseases and insects," "propagation," and so forth. Every plant referenced in the book's thousand pages put together in the same form. But, you can get lost in the book reading all these tiny "other notes" and trivialities. In reading about Buxus sempervirens, he introduces his list and inventory of "cultivars" noting where the best collections are and that he finds with Boxwood "...once they are put to the shears no one can reliably separate them." He follows this, in perfectly straightforward scientific prose, "There is an American Boxwood Society, [he gives the mailing address], that "Boxophiles" should consider joining if all other societies are full." He then offers what he finds to be the most important reference book in case you are deeply concerned with Boxwood taxonomy and culture. This isn't 1998 anymore so if you are one of these Boxophiles you just web search The Boxwood Society. Amazingly it is a real thing and on their website you can buy what they deem to be the most important books and compendiums on the Buxus genus. You'll find Boxwood Handbook: A Practical Guide to Knowing and Growing Boxwood (1995), by Lynn R. Batdorf as well as Boxwood: An Illustrated Encyclopedia by the same writer. This second book appears to be the most complete book on the topic, describing nearly 1100 species, varieties, and cultivars. It lists at $110. Confronted with these references, I considered buying the handbook, but asked myself, with what I do, "how much do I really need to know about Boxwood?" Plus, there is also this thing about specialty horticulture books - 80% of the book is the same information as every other horticulture book. Twenty percent most likely details and maps out how we understand all the different Boxwood in the world, and then the remainder of the book is filled with "How to Prune," "Understanding and Preparing the Soil," "Planting and Pruning Techniques," which as it turns out, really aren't specific to the species and are just common rules of horticulture. So - what did I come out of this with? I was looking to better familiarize myself with Boxwood. My initial engagement with plants and namings aren't in the nursery anymore - this way of being in the business has for the most part disappeared - but happen with the catalog being my first contact with specific names. And so, I need to make sense of what is presented in books and catalogs and then impose these sense makings onto the distant nurseries and imagine them into the garden. My process here in this study begins trying to make sense of what is available to me "in production," "in commerce." I need to understand all these possibilities available to me from Nurseries that aren't in my backyard so that I can design with them and order them. I printed out or copied the Boxwood pages from the grower availability lists I deal with and had them in front of me as I read through Dirr. For the most part, the Boxwood we would work with here in the Buffalo and Upstate New York area are of two different Boxwood species. Buxus microphylla is a Japanese native and the species is generally composed of varieties and cultivars that only grow to a couple, few feet tall and wide. B. sempervirens, which tend towards larger forms, some up to and beyond twenty-five feet in height, is a native of southern Europe, northern Africa, and western Asia. A good number of the cultivars in commerce are hybrids of the two, a cross between Korean variety of Boxwood and the sempervirens. Understanding the difference between 'a variety' and 'a cultivar' is important to the taxonomic differences here. The Korean Boxwood used to hybridize with sempervirens is a variety. It is written like so: Buxus microphylla var. koreana. A variety is a further identifiable grouping within the species - in this case microphylla - that reproduce themselves in nature, in the wild. A variety often comes from and has its own distinct geographic range. We see the following varieties within the microphylla species: var. koreana, var. japonica, var. sinica, var. insularism. Most important to the variety is that it is found in and reproduces itself in nature, in the wild, as opposed to the 'cultivar' which exists, having its own identifiable characteristics, as a result of its cultivation by humans. A cultivar is written: Buxus sempervirens 'Rotundifolia.' A variety if 'of the wild.' A cultivar is of the nursery, the farm, the garden. Further note - I am following Dirr's work and writing on this. Plant nomenclature is one of those things that is argued and has ever higher and higher rules. So. To try and describe what a variety is; well, my description is one that allows us to understand Boxwood in commerce. But there is also a conversation about subspecies. To do this proper, we would need to argue about the difference between variety and subspecies and from the basic readings I've done on this - well, that's a job for another day. 2/24/2021 Conference Review.1. Top Ten Disease and Insect Problems in NYS. |

AuthorFrom Matthew Dore, the "I" voice of Buffalo Horticulture and "The Buff Hort Project." Archives

April 2022

Categories |

Telephone(716)628.3555

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed