|

4/22/2022 Mississippi Street Hicks Yew HedgeA.

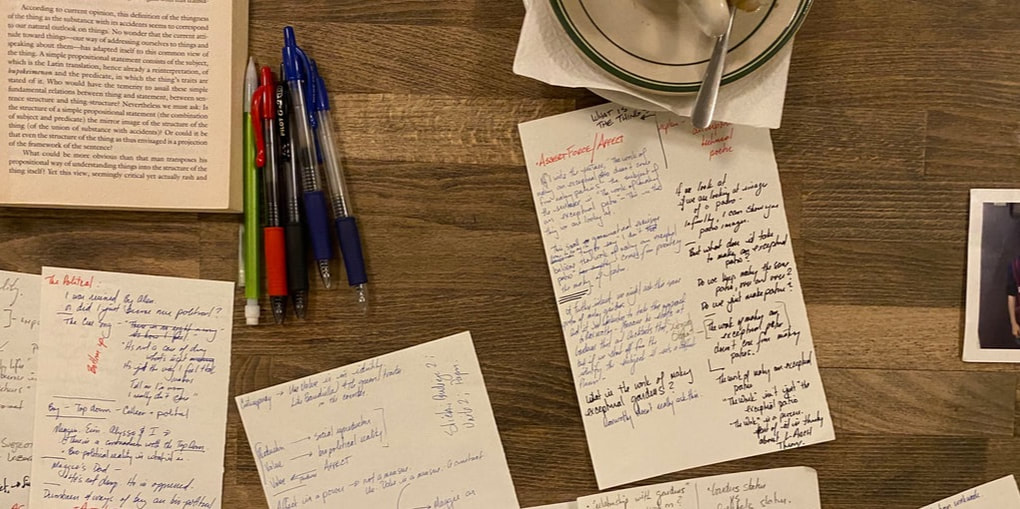

In the many years I have been contributing to this blog and journal oftentimes I have declared some new writing methodology I am using to help with my work. I think "new methodology" has become a constant experiment with new forms - "new forms of articulation." The standard essay has of course been used, personal narratives and biographies, "non paragraph forms," - poems, lists, bullets, etc. - and now, at the bottom, the "Story in 5 sentences." The story in 5 sentences hopes to reduce the articulation to the minimum content needed to elucidate the problem as I can't bring myself to express the problem without a payload of personal emotion and affectations. B. Each spring I arrive and find this hedge tattered and browned. I spend and hour or more combing through it, tipping out the brown. Years ago, it took a few minutes, but I would find in close inspection the large numbers of dead and discolored branches weren't some disease or salt injury but were all micro fractures and abrasions from the snowplow truck that clears the sidewalk here. After the attendance, taking out the browns, and making some hard cuts to stimulate some fresh buds and growth, I would watch the hedge green up again through the season and leave it in the fall with optimism we were making a hedge. C. 5 Sentences (to keep out the emotion).

3/17/2022 Pruning Hydrangea: Hydrangea macrophyllaSome riffs:

(A.) I planned on pruning these Hydrangea late in the spring. Yes - textbook, you prune them in "late summer after flowering" as they flower on old wood...but...I think that idea must come from the practice where you are just blindly cutting the plant back? As if, you cut the plant back hard "after if flowers," late in the summer, and this gives the plant enough time to push out some new growth before the season ends, on which of course, there will have formed flower buds for the next season. But this is Buffalo, NY and the traditional, old-school Hydrangea macrophylla doesn't often have its primary flower buds survive the winter. More often than not the flower buds are killed off by winter and early spring cold. AND...I don't know about you, but I think we appreciate the form and color of the faded Hydrangea flowers well into the fall and early winter...so we don't cut them back, we don't deadhead. Furthermore...I believe a good portion of the macrophylla offered in the nursery trade locally are what we would call "rebloomers" - these contemporary cultivars put out flower buds on both old and new wood and therefore, if the buds on old wood are killed off over the winter the Hydrangea still will flower later in the year on new wood. (B.) So...I'm pruning now (this morning), in late winter/early spring. I am not cutting back or reducing the plant in size, I'm essentially just cleaning. These Hydrangea get filled with deadwood pretty quickly. And, seemingly, as a rule, anytime anyone does prune them, they just top branches (I suspect in late summer!) about 8" off the ground and it leaves behind this mat of dead stubs that clutters the base. When cleaning up in the springtime - since we don't deadhead - the flowers from last season need to get cleaned up ("need" meaning, for visual reasons; for order) - and often the snow and perils of winter have broken a good portion of the branches still holding on to last seasons flowers... (C.) - I suppose it possible, at times with MATURE plants, a good hard rejuvenation prune - in late summer - may be helpful to give them a fresh start and a reason to vigor (not really a verb...but...). Method This was a sizable project (today's: depicted in images above) taking about 90 minutes in deep focus to prune this cluster of 7 plants. In this garden, there are still another 20 to 25 macrophylla to prune. I performed the work with earplugs in, something I like to do so as to keep me in a meditative space. I need standard hand pruners only,. I've been using Coronas this season, not Felcos. $24 a pair vs $60 and the same cut as far as I can tell. I go through 2 or 3 pair a season, so, it's relevant. I start at the tips closest to me combing through one branch at a time. If it has a old flower, I cut it off to the next bud. Many branches won't have a flower but a large pointed terminal bud. Chances are its cooked from the winter, but you can't really tell for sure, so I leave it. Any breaks I take back to the highest bud. I go down each branch and eliminate the dead laterals. I get down to the ground and I clear out all those dead stubs and the number of full length dead branches. For the most part, this is it, just deadwooding, but every so often there is a crossing branch I take out or "other things" that I don't like - but this is very minimal. Today.

Weeping Mulberry doesn't seem to find its potential around this region but, elsewhere, I see it as a well pruned winter sculpture. I have a couple that I am able to work with but there is always a "conflict" with the client - they can't help but take trimmers and pruners to it and hack it back during the summer months when it grows super fast. The aggressive and control oriented pruning always leads to the heavy production of buds and shoots; 18 months later the tree is a mess. With the two I worked with today...we are starting with one of those messes. Method: One can't cut at a Mulberry heavily - it will just cause a violent bud/shoot reaction. At the same time, we're starting with a mess - there are 1 to 2 inch branches crossing each other throughout the body of the crown. So, I allow myself two to three "big cuts" on each tree but keep them deep in the interior where they MAY be less likely to push buds (my speculation as there is little sun in there and everything on the inside is already dead) and only one "big cut" on either of the major skeletal branches. We'll deal with the fallout from this, if there is any, later. After these big cuts, I only cut out deadwood. End Note: Every pruning job like this, regardless of the species, is moves based on speculation of how you think the plant/tree will react - it's an art, but it may be best to use the term "informed practice" before we turn loose someone's creativity. "For me, a good plant fulfils a specific function in the garden, and does it well."

In the literature I read of plants being used as Function, not poetry. In the world of production Plants may function by Sequestering carbon or cleaning the air. Plants may be used to draw lead out of the soil - Stabilize the bank of a stream or river - Break the wind, fix nitrogen, or protect The topsoil of a farm that lay fallow. But in the garden Plants are not technical objects. Plants may “do” something They signify, make allusions, affect But they don’t function. (I am drawn to the word “Gesture.”) Beware of false prophets Who write of plants that function. This is engineering speak Not poetry, design, nor gardening. 10/29/2021 A Frame For Landscape PruningBird, Richard. The Illustrated Practical Encyclopedia of Pruning: Training & Topiary. Lorenz Books, Leicestershire, 2012. IBSN-13: 978-0-7548-2466-4 IBSN-10: 0-7548-2466-7 While my recent work has been interested in the literature on shearing, hedges, and simple topiary, these practices fall into the craft of pruning. My interest, or criticism, has been taking the position that “pruning” - as I see and hear it spoken of and identified with by horticultural enthusiasts around me - is a specific “register” of interest that attaches itself to a larger belief system about the landscape, nature, plants, art, work, knowledge, and history. We may go as far as to say “Its a power form.” I believe all our “pruning” practices find their origin in fruit production, the management of boundaries and property lines, and the production of wood and timber. The ornamental only emerges from these as aesthetics. What has captured me about Bird’s book on pruning is its full inventory of all the different practices we can name in the training of plants. I thought it a good idea to list this inventory in my notes as it gives a good context to the field of training/pruning plants and very much diminishes the great importance ornamental horticulturists put on their pruning practice. Or, with an inventory, it frames the pruner/landscaper as a very limited field of practices.

7/10/2021 The Practice.Pruning is a poetic movement.

The truth of the practice reveals itself only in practice. It is the practice itself that is concealed - The novice is paralyzed - Their action aims to make form into a previous image, Where as the poet only moves to articulate the practice. The practice is the truth. 6/28/2021 Pruning From The Inside.To maintain trees at a certain size

For it to maintain "that quality" of a tree It has to be pruned from the inside Following more of a methodical process That moves in an understanding of growth. But first In what may take a couple years - An architecture of branches must be created. Then one can return on intervals And make cuts repeatedly In method. Part of the architecture is about creating a structure that can be returned to again and again and easily reduced to its managed form. One's cuts are much lower than if you were approaching from outside the crown. From here growth sprouts and grows. You can't teach pruning. There are some principles - You must know how growth and buds form in reaction to cuts - It is a poetic. I had my shears in hand Monday, ready to go through all the garden's formal plant elements and tighten them up - but as I stepped to the first plant I said to myself, "I don't need to spend an hour doing this now." It is/was early May, mid spring, and the new growth is just forming. This is the time to "shape" not trim. By this I mean, (this being a garden I was tending for the first time) it was a time to make heavier, deeper shear cuts to "address geometry," not manicure. Early in the season, plants will more aggressively push new buds in response to heavy pruning cuts, so this is the time for some deep disciplining. "Trimming" and "manicuring" is more of a maintenance practice to be done anytime. But this type of maintenance shearing is light and more about an immediate presentation of the garden than making the garden.

“I don’t know why my Hydrangeas don’t flower” is one of the great conundrums that are handed to me by clients. As with all things, I never know exactly, nor do I have an clear answer, I can only offer that coming to understand these things takes place in the process of experiencing and working with the garden. This question almost always comes while looking upon a Bigleaf Hydrangea (Hydrangea macrophylla). Immediately one asks how it may have been pruned, the gardens history and care, considers the soil, and how cold it was the past winter knowing that Hydrangea macrophylla often experiences tip dieback where you loose the flower buds to the winter’s cold.

A week or two ago I ordered Michael Dirr’s latest edition of “Hydrangeas for American Gardens” (2020) to begin a little study on Hydrangea. I am finding them becoming so popular, even in my own preferences, that some study is a worthwhile investment. At least at the start of this, it was Hydrangea paniculata and its cultivars that I am most interested in. However, a little tidbit caught me while reviewing Dirr's work on Hydrangea: Bailey (1989a) provides climatic data for the native habitats that explain Hydrangea macrophylla sensitivity to certain extremes. Honshu enjoys more than 5 months of frost free temperatures. The mean low and high temperatures are 31 and 47 degrees F in January and 72 and 85 F in August, respectively…The conclusions are obvious: H. Macrophylla prefers moderate temperatures…(73). Most of Dirr's writing on macrophylla is based on studies done at his University in Athens, Georgia and from research done in North Carolina. Even at those southern locations, some of the named cultivars he writes of as not surviving the cold are names I recognize as macrophylla cultivars in WNY nurseries. From this I leapt to: “All these Hydrangea I see that don’t flower - they probably just aren’t hardy enough to begin with.” So. I thought I would do a little research on the cultivars most readily available to me right now and find what research I could on hardiness data. One key is understanding the “remontants” or re-bloomers. These bloom multiple times because they will bloom on this seasons new wood as well as older wood. A hydrangea that doesn’t bloom on new wood is dependent on old wood to over winter for its flower buds. When they are killed off by frost, no flowers. But with re-bloomers, the old wood can die back to the ground but still produce flowers that season on its new wood. I believe most traditionally we think of Hydrangea macrophylla as a plant that "blooms on old wood." The Study: Generally, and this is new to me, it seems that plant breeders characterize Hydrangea macrophylla as “undependable.” Thus my curiosity of "why is this such a commonly used plant in WNY?" To disclose, this isn't the deepest research. A few hours. I made the best sense of things reading a couple blogs, Dirr's latest edition of "Manual of Woody Plants," Dirr's latest on Hydrangea's, and a few wholesale catalogs and nurseries I have here in the office. Here is what I have found on the cultivars:

What I generally find in the literature combined with my experience is that Hydrangea macrophylla's flower buds, those on old wood, are most often probably killed off. A Hydrangea can be listed as cold hardy zone 4 (for example) but this just means the plant survives, it doesn't mean the flower buds survive. It seems that even all the new rebloomers and remontants, while exciting in concept, they generally seem to be written of as disappointing - however the most recent 'Bloomstruck' series appears to be the best yet and worth my experimentation. The thing with a rebloomer is, it becomes a plant that blooms on this season's wood, and thus later in the season, which means a shorter flowering season. It seems the recent improvements in Hydrangea arborescens are perhaps more worth exploring. Just some notes. Post Script. April 6th, 2021. I have been watching the Hydrangea this spring. I can see that possibly the buds on the tips get through the winter as they have the opportunity to acclimate to the deep cold of winter. But now, the beds are starting to swell at the end of March, beginning of April. The inevitability of a hard frost here in early April - well - these swelling buds are probably most susceptible to frost/cold damage now. More so now than the first week of February. 3/4/2021 Morning's Notebook.Some notes and bullets.

|

AuthorFrom Matthew Dore, the "I" voice of Buffalo Horticulture and "The Buff Hort Project." Archives

April 2022

Categories |

Telephone(716)628.3555

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed