|

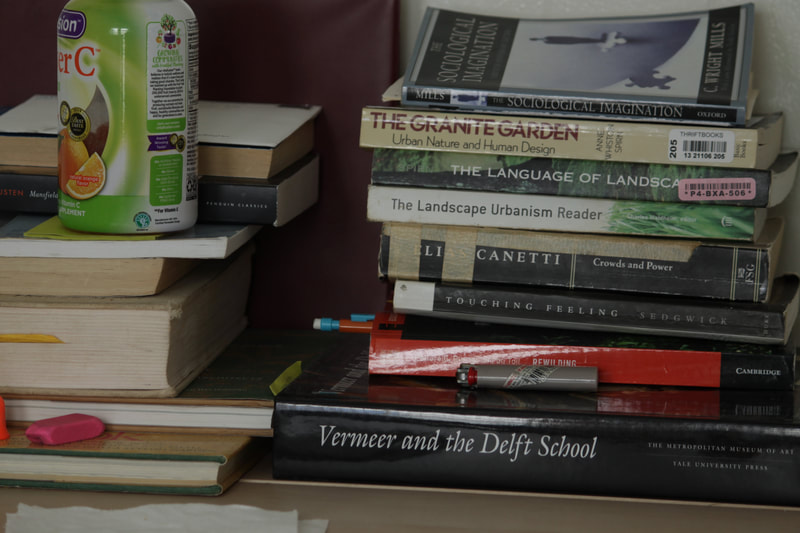

4/25/2020 On "The Buffalo Horticulture Project"There is an old essay written back in the late-50s by C.W. Mills titled, "On Intellectual Craftsmanship." I have wanted to write about it for all of time here on "Border Gardening" as it is from this essay "The Buffalo Horticulture Project" takes its inspiration. But it is complicated to write about. First off, the essay is written to graduate students in social science, not to gardeners. Secondly, I am always criticized for making things too intellectualized; and so finding a way to talk about the essay as a spirit of work, not sociology, becomes intellectual and I can never narrate through the problem.

...social science is the practice of a craft. A man at work on problems of substance, he is amongst those who are quickly made impatient and weary by elaborate discussions of method-and-theory-in-general; so much of it interrupts his proper studies. (195) For the longest time I read the essay as about "How to do sociology." It was a methods text given to me by a professor very interested in the work I was doing - he had never had a student write gardening and landscape stories as sociological analysis before. I don't think I came to realize until 6 months ago that he never gave me the book to think about sociology. He gave it to me to think about craftsmanship and study, the questions I was really raising in my work - questions of value. Although Buffalo Horticulture has been around since 2001, since I left the family business, it has gone through many phases of life. There were the early years where I was still tied with the old world. Then there was the years of Peter and Emily. It was different then. I wasn't the designer, Emily was. Then there was the graduate school years where things slowed down in production. There was this moment of fantasy about being a working-class scholar - but no one wanted me to be a professor. From this emerged what I titled five years later, "The Buffalo Horticulture Project," - my life's work. I study and practice. ...the most admirable thinkers within the scholarly community you have chosen to join do not split their work from their lives. They seem to take both too seriously to allow such disassociation, and they want to use each for the enrichment of the other. Of course, such a split is the prevailing convention among men in general, deriving, I suppose, from the hollowness of the work which men in general now do. But you will have recognized that as a scholar you have the exceptional opportunity of designing a way of living which will encourage the habits of good workmanship. Scholarship is a choice of how to live as well as a choice of career; whether he knows it or not, the intellectual workman forms his own self as he works toward the perfection of his craft; to realize his own potentialities, and any opportunities that come his way, he constructs a character which has as its core the qualities of a good workman. I will finish saying this: Buffalo Horticulture builds and cares for people and the landscape. It is a way of living. There are a lot of people who chose to live this life. It has a spirituality, an atmosphere. It is a way to find satisfactions in an occupation that is not typically "of high value." I am not the only one in the green industry who lives this way Although there are several. We are definitely a minor literature. I am the only one with a graduate degree in social theory and so I know others who share the same commitment and life choices And love But aren't necessarily able to find the same kind of voice I do. In the horticulture and landscape professions right now There is an unspoken of divide. So much political conversation about "The Essentials"... I think it is helping us form a group identity Often just lost in the word "landscaper." The struggle with an ambiguous State definition of "essential" makes for a unique anxiety; One that clearly has concerns different from "business" and more with "life." I wrote in a design intent/program that I sent out this morning:

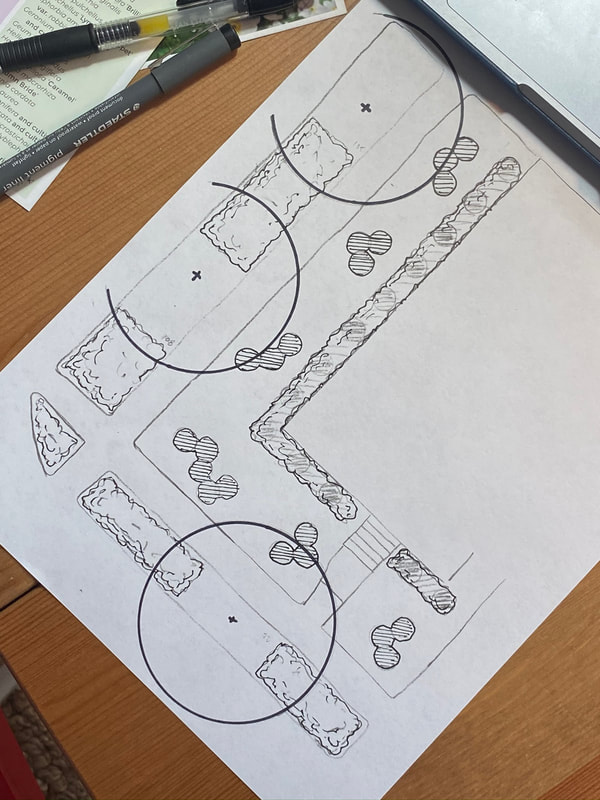

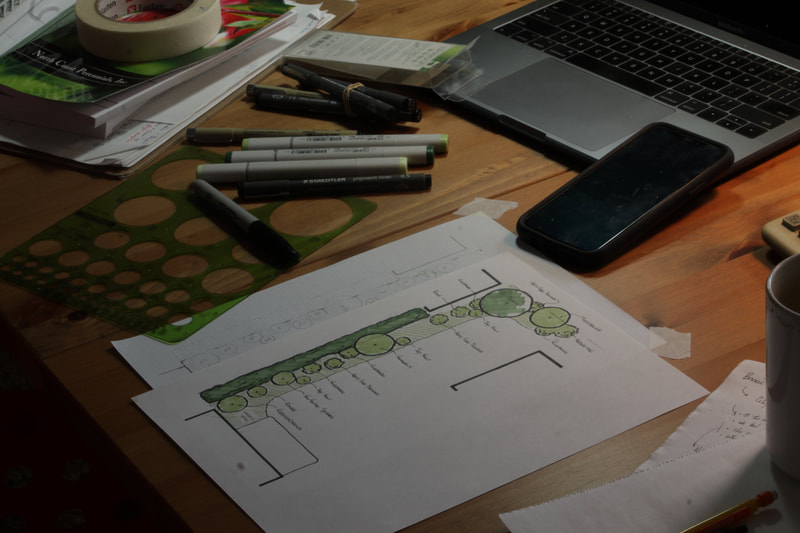

I attempt to create a garden with all season interest as well as a garden to engage with in different ways than just visually. Quince, VanHouttei x Spiraea, Hamamelis, and Flowering Dogwood, are used as part of the "shrubbery structure and form" of the garden, as unique seasonal interests and specimens, which can be pruned from during the late winter and spring for branch forcing indoors. Multiple Ninebark and Arctic Fire Dogwood contribute rhythm and repetition to the mass and shrubbery structure. The Ninebark is a nice summer branch harvest and the Arctic Fire Dogwood is commonly used with early winter and holiday decor. I am always sharing images, be it on media or here in the blog and journal, of my branches, flowers, and arrangements here in the office. But when I do, it isn't just empty content; it isn't aiming to be one of these fashion 'gram pages that just makes everyone feel their life isn't good enough; it isn't creating "the Buff Hort aesthetic," which is one of the most ridiculous things I hear young business people concerned with. The point of this all is to show a way of life that interacts with the garden. Cutting materials gets someone in contact with the garden, it becomes a play space, they become more aware of seasonal flowering sequences, see the importance of branching structures, and so on. While I do buy in some flowers every so often (Madelyn's Floral and Farm in Hamburg, the occasional Aldi Bouquet, Wegman's Tulips, Farmers Markets) for the most part everything comes from my garden, a garden I work on, or an innocent forage somewhere - for the most part, it is a super cheap way to live, get creative, learn, and try to make beautiful things. This weeks images: The following is an addition to works I have been assembling the past two weeks that consider our work in the larger Buffalo Horticulture community in the context that is considering “what work is essential,” during the COVID-19 pandemic, as we all distance ourselves during “NY Pause.” Just yesterday I put together a quick design study for the owners of a corner lot house in the Elmwood Village. The study was to consider possible solutions and feasibility for a lawn and yard - the public space between the house's foundation and the curb - that is currently spotty patches of fescue, dirt, moss, weeds, and a well established colony of Lesser Celandine. There are three street trees around the house, two of which were Norway Maples that cast a heavy shade, occupy the root zone, and evaporate water out of the soil not leaving any to share with other plants. As these street trees have grown over the past 30 to 40 years or so, their increasing dominance of resources has led the traditional turfgrass of the lawn below to decline. “The Lawn” in our garden culture refers to the maintained space of turfgrass, while I believe in the English tradition it refers to the garden space as a whole, including gardens and turf. This is important to distinguish because here “lawn” specifically points to a plant, grass, that is grown in large uniform quantities over an expanse. Whereas, another use, one always used by clients here in Buffalo that move in from out of the country, “lawn” is used to point to a space, “the front lawn.” I will be asked to work on the lawn, but the ornamental plantings of the foundation, not the grass. As I considered the costs and how we may consider the value of this project I thought about what kind of expenses we may, without question, be willing to incur for other surfaces and projects in a house - costs of flooring, finishing walls, basement floors, roofs, etc. “Why do we privilege those surfaces so much? Why do we spend $10 a square foot on those surfaces but are only willing to spend $6 per square foot in lawn and garden.” This soon raised the question of “the cosmetic,” a trigger word right now in landscaping as with the “NY Pause” program that responds to the pandemic, we have deemed landscape maintenance “essential,” but no new installations, “nothing cosmetic.” This project brings some of our thinking about landscaping, installations, and the cosmetic into conflict. To think of this potential new lawn as cosmetic goes along with a thinking that we are here engaged in the practice of “having nice things,” and so we will install a new lawn to give us all the “extras” - “it just looks nice” - that come with that nice thing. This cosmetic sense opposes what is seen as essential. Now is not the time to make “something more.” Now is a time for maintenance, protect the values you have. Bonnie Guckin and Tom Draves have both said this to me: “as if we are ever just going around doing things that aren’t essential.” This sentiment is trying to get us outside of a dominant way of thinking, outside of “make new/maintain.” To me this is the conflict with this “lawn” project. I see it as lying completely outside of this dichotomy. It is pointing towards what Bonnie, Tom, and I are continuously speaking of in this “NY Pause,” pandemic, “only essential work” situation. The work we do is thought of as only “cosmetic.” I think this lawn project helps us get towards an articulation of our problem, a difficult place to get to as it is outside everyday and dominant language and thinking. A lot of the spaces we are being called upon to look at right now are not for people who want to make something extra, something new, so they can have nice things (thinking of a Taylor Swift song), but they recognize this lawn space as less than healthy and as part of their home: it is in their domain of care giving. And here, to do “new work” on this lawn, isn’t “new work,” but caring for and attending to the existing space. It thinks in a world without maintenance and in a world of caring for. It is non-essential work. These are the spaces of critique opened up in the pandemic. In small business where the owner/proprietor is the doer of just about all things, a month or two long slow down because of a global pandemic can give them the space to get done some of those tasks way deep down on the task lists that are never gotten to. I have pulled off some pretty major restructures in the past month with the additional office time but also find myself creatively procrastinating by "seeing things" I should photograph. There are a lot of stories to tell here around the home/office/studio space, but most of them - like the flashlight shots - aren't very interesting except to the smallest of niches.

The reorganizations of production have pretty much happened at this point and now I am back up at full speed. A topic that came up this week was the practice of cosmetic mulching. It is difficult to sort through as the majority of mulch put down and spread may in fact be IMAGINED as just that, cosmetic.

In the business, it seemed everyone this week was racing to find the science to prove how essential mulching was as the County Executive had declared "no mulching, its not essential; only maintenance." I didn't have to look it up. It has been there forever but I had all these people sending me bits and pieces - "I found this document on mulch from the Alabama Cooperative Extention!" or "Look! Cornell says mulch has all these benefits." This is part of our complication. Mulch does many things, depending on what you mulch with. All mulch will help insulate the soil and moderate soil temperatures; moisture is held in the soil and its evaporation prevented by a blanket of mulch. Root crowns are protected. Erosion from heavy rains that expose roots is prevented. These are almost what we may just call "mechanical and technical benefits." From there different mulches can do different things. Peat Moss will reduce a soils pH, improve a soil's structure, and aid in moisture retention. Compost probably brings the most fertility and in the organic practitioners' practice, is used to manipulate and encourage biological activity that will suppress diseases, provide harbor to beneficial microfauna keeping pest populations in control, as well as influencing the bacterial and fungal relationships in the soil that dictate what forms of nitrogen become available to plants. Gravels are also a mulch and work best where there may be a lot of foot traffic or erosion potentials. Shredded Hardwood bark gives one all the mechanical advantages of mulch while also having superior weed suppressing abilities. A landscape garden, in all reality, HAS TO BE covered in a mulch. If you leave a bare soil open you will find that within few weeks time it will be covered in spontaneously germinated weed plants. But. As horticulturists, we already know this and it structures our practices. "Mulching" - a very important word here - as a verb form, indicating it is an act performed, goes back to the middle of the 1700s where the word was used for the first time. I may speculate that the first mulches were leaves, sticks, or any coarse material one could find and it would be placed around whatever it was that was trying to be grown, most likely small scale food crops. The way we often talk about mulch now is in the context of ORNAMENTAL landscapes and gardens. A conversation as to whether mulching is essential therefore needs to consider exactly what is being done when mulching. When I was a kid, there was only decorative gravel, bagged Pine Bark Nuggets, and bales of peat moss commercially available. Soon, in the late 80s, shredded bark started to become a thing. Even since then, the material qualities produced in a shredded bark mulch have changed in a big way. It used to be course in texture and a rich brown color was considered the highest quality. Reddish mulch became available locally in bags. Then "Black Gold" which was near black became available, and in the last 10 years now, we have seen massive capital investment in mulch shredding machines that inject colored dyes to artificially influence the color. I remember long ago, my grandparents house, in the back yard, behind a tall sheered Privet hedge and a gate, was a garden and compost bin where all the yard waste and food scraps went. The compost was recycled as a mulch. Mulch, like the early use of leaves, sticks, or mosses, was what material was available for "mulching." It was a practice of gardening. Now, tall pallets of bagged mulch await homeowners at every 7-11 and gas station. People want specific mulch, "I want black mulch," because it has become what looks nice to them. In many ways, someone doesn't need to know how to design a landscape - a good layer of mulch can look as nice as anything. But there are still out here horticulturists that depend on mulch to hold weeds down, hold moisture in, protect, and grow plants - without which would lead to a large increase of work to maintain the garden. To the horticulturist and gardener, to the growers of plants, the material spread as mulching is as much a tool as fertilizers, pesticides, or round-up, only it's, we'll say, a more local solution. To the growers mulch is an essential tool to sustaining a landscape. To others, with a different practice and imagination, the mulch is itself what looks nice. It doesn't do anything, it is only cosmetic. Mulch is a material that for the gardener does something. Over time garden practice has led to advancements in and the development of better mulch materials, finer textures, richer colorings - but so far as to where the material development itself has taken over, to where often it appears the dominant form of gardening now excludes the plants and finds all its pleasurable experiences in just the aesthetics of mulch. The pleasing experience people now how have with mulch is the end point of the development of a field of work, a craft, where artists, or gardeners, of craftspeople, what ever you wish to call them, have over a period of time, refined and processed their materials - mulch - and learned dexterities and techniques to smooth and spread - mulching. But now, I am finding myself in a historical place where I am told not to mulch because it is ONLY aesthetic, cosmetic. I am happy to comply with the law, but it is pretty degrading to a horticulturist's practice and everything they know and believe, to be forced into this loyal acquiescence. Cosmetic mulching in many ways embodies a hundred years or more of the development of human skill and intelligence in gardening. Its experience elevated the material technology to where "mulching" has become a separated professional specialization, disconnected entirely from a relationship with plants. It is the modern cultural form. But there are still horticulturists and growers. Not many. |

Matthew DoreLandscape designer and Proprietor of Buffalo Horticulture Archives

April 2020

Categories |

Telephone(716)628.3555

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed